1. Van . “The Cumulative Cost of Additional Wakefulness: Dose-Response Effects on Neurobehavioral Functions and Sleep Physiology from Chronic Sleep Restriction and Total Sleep Deprivation.” Sleep, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12683469/.

2. Caia. “Does Self-Perceived Sleep Reflect Sleep Estimated via Activity Monitors in Professional Rugby League Athletes?” Journal of Sports Sciences, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29087784/.

3. DF;, Lim. “A Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Short-Term Sleep Deprivation on Cognitive Variables.” Psychological Bulletin, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20438143/.

4. Watson . “Recommended Amount of Sleep for a Healthy Adult: A Joint Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society.” Sleep, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26039963/.

5. Nedeltcheva. “Insufficient Sleep Undermines Dietary Efforts to Reduce Adiposity.” Annals of Internal Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20921542/.

6. SD;, Wang. “Influence of Sleep Restriction on Weight Loss Outcomes Associated with Caloric Restriction.” Sleep, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29438540/.

7. Donga . “A Single Night of Partial Sleep Deprivation Induces Insulin Resistance in Multiple Metabolic Pathways in Healthy Subjects.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20371664/.

8. Shechter . “Alterations in Sleep Architecture in Response to Experimental Sleep Curtailment Are Associated with Signs of Positive Energy Balance.” American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22972835/.

9. Zhu, Bingqian. “Effects of Sleep Restriction on Metabolism-Related Parameters in Healthy Adults: A Comprehensive Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.” Sleep Medicine Reviews, W.B. Saunders, 10 Feb. 2019, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1087079218301941.

10. Bosy-Westphal. “Influence of Partial Sleep Deprivation on Energy Balance and Insulin Sensitivity in Healthy Women.” Obesity Facts, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20054188/.

11. Al Khatib, Haya K. “Sleep Extension Is a Feasible Lifestyle Intervention in Free-Living Adults Who Are Habitually Short Sleepers: a Potential Strategy for Decreasing Intake of Free Sugars? A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study.” OUP Academic, Oxford University Press, 10 Jan. 2018, academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/107/1/43/4794751.

12. J;, Orzeł-Gryglewska. “Consequences of Sleep Deprivation.” International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20442067/.

13. Buxton . “Adverse Metabolic Consequences in Humans of Prolonged Sleep Restriction Combined with Circadian Disruption.” Science Translational Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22496545/.

14. N;, Spaeth. “Resting Metabolic Rate Varies by Race and by Sleep Duration.” Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26538305/.

15. Pilcher, June J, et al. “Interactions between Sleep Habits and Self-Control.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, Frontiers Media S.A., 11 May 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4426706/.

16. Clark, Alice Jessie, et al. “Onset of Impaired Sleep and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors: A Longitudinal Study.” Sleep, Associated Professional Sleep Societies, LLC, 1 Sept. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4989260/.

17. Lange, Tanja, et al. “NYAS Publications.” The New York Academy of Sciences, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 13 Apr. 2010, nyaspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05300.x.

18. Leproult . “Sleep Loss Results in an Elevation of Cortisol Levels the next Evening.” Sleep, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9415946/.

19. Leproult, Rachel, and Eve Van Cauter. “Effect of 1 Week of Sleep Restriction on Testosterone Levels in Young Healthy Men.” JAMA, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 June 2011, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4445839/.

20. Eve Van Cauter, PhD. “Age-Related Changes in Slow Wave Sleep and REM Sleep and Relationship With Growth Hormone and Cortisol Levels in Healthy Men.” JAMA, JAMA Network, 16 Aug. 2000, jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/192981.

21. L;, Van. “Physiology of Growth Hormone Secretion during Sleep.” The Journal of Pediatrics, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8627466/.

22. Alhola, Paula, and Päivi Polo-Kantola. “Sleep Deprivation: Impact on Cognitive Performance.” Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, Dove Medical Press, 2007, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2656292/.

23. Zhu, Bingqian, et al. “Effects of Sleep Restriction on Metabolism-Related Parameters in Healthy Adults: A Comprehensive Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.” Sleep Medicine Reviews, W.B. Saunders, 10 Feb. 2019, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1087079218301941.

24. Charles. “Association of Perceived Stress with Sleep Duration and Sleep Quality in Police Officers.” International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22900457/.

25. Choi . “Association between Sleep Duration and Perceived Stress: Salaried Worker in Circumstances of High Workload.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29671770/.

26. Kohn, Taylor P, et al. “The Effect of Sleep on Men’s Health.” Translational Andrology and Urology, AME Publishing Company, Mar. 2020, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7108988/.

27. Knowles, Olivia E., et al. “Inadequate Sleep and Muscle Strength: Implications for Resistance Training.” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, Elsevier, 2 Feb. 2018, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1440244018300306.

28. Blumert . “The Acute Effects of Twenty-Four Hours of Sleep Loss on the Performance of National-Caliber Male Collegiate Weightlifters.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18076267/.

29. Dáttilo . “Effects of Sleep Deprivation on Acute Skeletal Muscle Recovery after Exercise.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31469710/.

30. Buysse, Daniel J. “Sleep Health: Can We Define It? Does It Matter?” Sleep, Associated Professional Sleep Societies, LLC, 1 Jan. 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3902880/.

31. Chandrasekaran, B., et al. “Science of Sleep and Sports Performance – a Scoping Review.” Science & Sports, Elsevier Masson, 26 June 2019, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0765159719300723?via=ihub.

32. Vitale, Kenneth C, et al. “Sleep Hygiene for Optimizing Recovery in Athletes: Review and Recommendations.” International Journal of Sports Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Aug. 2019, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6988893/.

33. Mah . “Sleep Restriction Impairs Maximal Jump Performance and Joint Coordination in Elite Athletes.” Journal of Sports Sciences, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31122131/.

34. Jåbekk. “A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial of Sleep Health Education on Body Composition Changes Following 10 Weeks’ Resistance Exercise.” The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32141273/.

35. Amstrup . “Reduced Fat Mass and Increased Lean Mass in Response to 1 Year of Melatonin Treatment in Postmenopausal Women: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial.” Clinical Endocrinology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26352863/.

36. Bisson, Alycia N. Sullivan, et al. “Walk to a Better Night of Sleep: Testing the Relationship between Physical Activity and Sleep.” Sleep Health, Elsevier, 26 July 2019, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2352721819301056?via=ihub.

37. Dolezal, Brett A, et al. “Interrelationship between Sleep and Exercise: A Systematic Review.” Advances in Preventive Medicine, Hindawi, 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5385214/.

38. Wang, Wei-Li, et al. “The Effect of Yoga on Sleep Quality and Insomnia in Women with Sleep Problems: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” BMC Psychiatry, BioMed Central, 1 May 2020, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7193366/.

39. Bankar, Mangesh A, et al. “Impact of Long Term Yoga Practice on Sleep Quality and Quality of Life in the Elderly.” Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine, Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd, Jan. 2013, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3667430/.

40. Halpern . “Yoga for Improving Sleep Quality and Quality of Life for Older Adults.” Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24755569/.

41. Ebrahimi, Mohsen, et al. “Effect of Yoga and Aerobics Exercise on Sleep Quality in Women with Type 2 Diabetes: a Randomized Controlled Trial.” Sleep Science (Sao Paulo, Brazil), Brazilian Association of Sleep and Latin American Federation of Sleep, 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5612039/.

42. Tworoger . “Effects of a Yearlong Moderate-Intensity Exercise and a Stretching Intervention on Sleep Quality in Postmenopausal Women.” Sleep, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14655916/.

43. D’Aurea, Carolina V R, et al. “Effects of Resistance Exercise Training and Stretching on Chronic Insomnia.” Revista Brasileira De Psiquiatria (Sao Paulo, Brazil : 1999), Associação Brasileira De Psiquiatria, 2019, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6781703/.

44. Hallegraeff . “Stretching before Sleep Reduces the Frequency and Severity of Nocturnal Leg Cramps in Older Adults: a Randomised Trial.” Journal of Physiotherapy, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22341378/.

45. Aliasgharpour, Mansooreh, et al. “The Effect of Stretching Exercises on Severity of Restless Legs Syndrome in Patients on Hemodialysis.” Asian Journal of Sports Medicine, Kowsar, 11 June 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5003313/.

46. Kovacevic. “The Effect of Resistance Exercise on Sleep: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials.” Sleep Medicine Reviews, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28919335/.

47. Mignot, E., et al. “Effects of Evening Exercise on Sleep in Healthy Participants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Sports Medicine, Springer International Publishing, 1 Jan. 1970, link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-018-1015-0.

48. Whitworth-Turner. “A Shower before Bedtime May Improve the Sleep Onset Latency of Youth Soccer Players.” European Journal of Sport Science, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28691581/.

49. Hutchison . “Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Glucose Tolerance in Men at Risk for Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Crossover Trial.” Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31002478/.

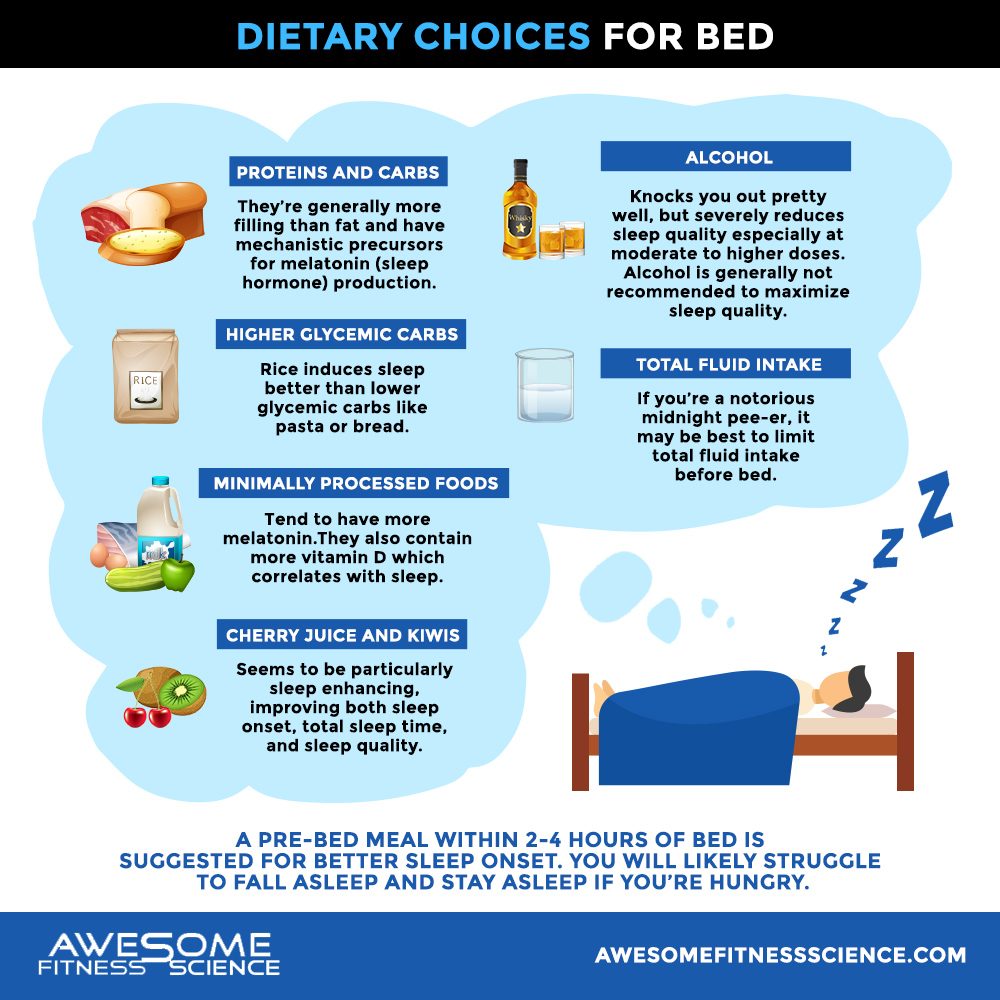

50. CM;, Afaghi. “High-Glycemic-Index Carbohydrate Meals Shorten Sleep Onset.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17284739/.

51. S;, Gill. “A Smartphone App Reveals Erratic Diurnal Eating Patterns in Humans That Can Be Modulated for Health Benefits.” Cell Metabolism, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26411343/.

52. JA;, Porter. “Bed-Time Food Supplements and Sleep: Effects of Different Carbohydrate Levels.” Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6164541/.

53. M;, Lindseth. “Nutritional Effects on Sleep.” Western Journal of Nursing Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21816963/.

54. RD;, Grandner. “Relationships among Dietary Nutrients and Subjective Sleep, Objective Sleep, and Napping in Women.” Sleep Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20005774/.

55. CM;, Afaghi. “Acute Effects of the Very Low Carbohydrate Diet on Sleep Indices.” Nutritional Neuroscience, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18681982/.

56. M. Foz, M. Barbany, et al. “Eating Carbohydrate Mostly at Lunch and Protein Mostly at Dinner within a Covert Hypocaloric Diet Influences Morning Glucose Homeostasis in Overweight/Obese Men.” European Journal of Nutrition, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1 Jan. 1970, link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00394-013-0497-7.

57. Yoneyama . “Associations between Rice, Noodle, and Bread Intake and Sleep Quality in Japanese Men and Women.” PloS One, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25127476/.

58. Meng, Xiao, et al. “Dietary Sources and Bioactivities of Melatonin.” Nutrients, MDPI, 7 Apr. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5409706/.

59. St-Onge, Marie-Pierre, et al. “Effects of Diet on Sleep Quality.” Advances in Nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), American Society for Nutrition, 15 Sept. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5015038/.

60. Howatson . “Effect of Tart Cherry Juice (Prunus Cerasus) on Melatonin Levels and Enhanced Sleep Quality.” European Journal of Nutrition, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22038497/.

61. JF;, Lin. “Effect of Kiwifruit Consumption on Sleep Quality in Adults with Sleep Problems.” Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21669584/.

62. Gao, Qi, et al. “The Association between Vitamin D Deficiency and Sleep Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Nutrients, MDPI, 1 Oct. 2018, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6213953/.

63. “The Relationship Between Lifestyle Regularity and Subjective Sleep Quality.” Taylor & Francis, www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1081/CBI-120017812.

64. Wehrens . “Meal Timing Regulates the Human Circadian System.” CB, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28578930/.

65. S;, Giannotti. “Circadian Preference, Sleep and Daytime Behaviour in Adolescence.” Journal of Sleep Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12220314/.

66. CI;, Baehr. “Individual Differences in the Phase and Amplitude of the Human Circadian Temperature Rhythm: with an Emphasis on Morningness-Eveningness.” Journal of Sleep Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10849238/.

67. Xu, X, et al. “Habitual Sleep Duration and Sleep Duration Variation Are Independently Associated with Body Mass Index.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 12 Sept. 2017, www.nature.com/articles/ijo2017223.

68. Monk, Timothy H. “Enhancing Circadian Zeitgebers.” Sleep, Associated Professional Sleep Societies, LLC, Apr. 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2849779/.

69. C;, Bonnar. “Sleep Interventions Designed to Improve Athletic Performance and Recovery: A Systematic Review of Current Approaches.” Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29352373/.

70. Boukhris, Omar, et al. “Nap Opportunity During the Daytime Affects Performance and Perceived Exertion in 5-m Shuttle Run Test.” Frontiers in Physiology, Frontiers Media S.A., 20 June 2019, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6596336/.

71. L;, Lovato. “The Effects of Napping on Cognitive Functioning.” Progress in Brain Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21075238/.

72. Mantua, Janna, and Rebecca M C Spencer. “Exploring the Nap Paradox: Are Mid-Day Sleep Bouts a Friend or Foe?” Sleep Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Sept. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5598771/.

73. KA;, Milner. “Benefits of Napping in Healthy Adults: Impact of Nap Length, Time of Day, Age, and Experience with Napping.” Journal of Sleep Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19645971/.

74. McDevitt, Elizabeth A, et al. “The Impact of Frequent Napping and Nap Practice on Sleep-Dependent Memory in Humans.” Scientific Reports, Nature Publishing Group UK, 10 Oct. 2018, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6180010/.

75. Anderson, Travis, and Laurie Wideman. “Exercise and the Cortisol Awakening Response: A Systematic Review.” Sports Medicine – Open, Springer International Publishing, 10 Oct. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5635140/.

76. Takahashi, Joseph S. “Transcriptional Architecture of the Mammalian Circadian Clock.” Nature Reviews. Genetics, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Mar. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5501165/.

77. DJ;, Viola. “Blue-Enriched White Light in the Workplace Improves Self-Reported Alertness, Performance and Sleep Quality.” Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18815716/.

78. B;, Fetveit. “Bright Light Treatment Improves Sleep in Institutionalised Elderly–an Open Trial.” International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12789673/.

79. MW;, Campbell. “Alleviation of Sleep Maintenance Insomnia with Timed Exposure to Bright Light.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8340561/.

80. LA;, Sanassi. “Seasonal Affective Disorder: Is There Light at the End of the Tunnel?” JAAPA : Official Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24394440/.

81. T;, Tuunainen. “Light Therapy for Non-Seasonal Depression.” The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15106233/.

82. Golden . “The Efficacy of Light Therapy in the Treatment of Mood Disorders: a Review and Meta-Analysis of the Evidence.” The American Journal of Psychiatry, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15800134/.

83. Hsouna, Hsen, et al. “Effect of Different Nap Opportunity Durations on Short-Term Maximal Performance, Attention, Feelings, Muscle Soreness, Fatigue, Stress and Sleep.” Physiology & Behavior, Elsevier, 3 Sept. 2019, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0031938419304433.

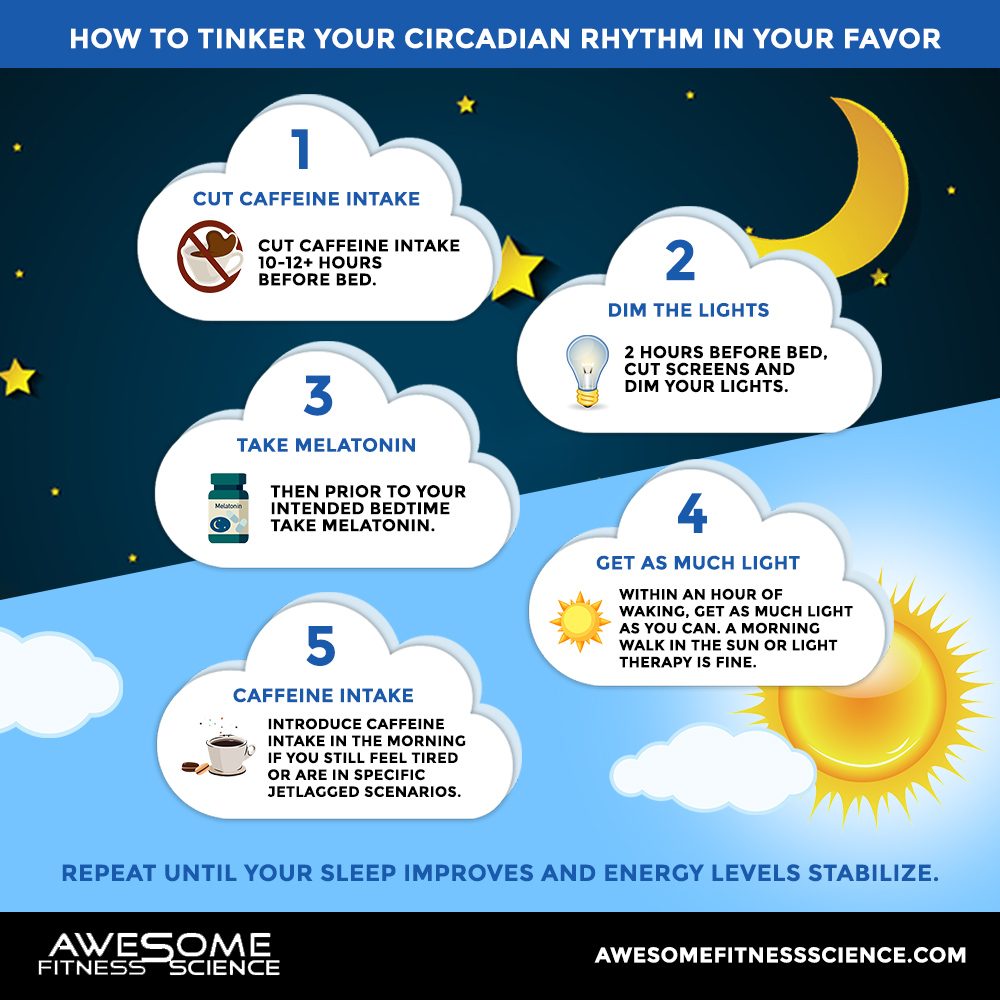

84. Gooley, Joshua J, et al. “Exposure to Room Light before Bedtime Suppresses Melatonin Onset and Shortens Melatonin Duration in Humans.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, Endocrine Society, Mar. 2011, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3047226/.

85. A;, Cajochen. “Evening Administration of Melatonin and Bright Light: Interactions on the EEG during Sleep and Wakefulness.” Journal of Sleep Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9785269/.

86. Cain, Sean W., et al. “Evening Home Lighting Adversely Impacts the Circadian System and Sleep.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 5 Nov. 2020, www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-75622-4?fbclid=IwAR0M8G5b831LPSJXHcvi0-j-pl7e9uWlhnqB6uyd2dgpJ8yC7mggkbNuEQY.

87. Brown, Timothy M. “Melanopic Illuminance Defines the Magnitude of Human Circadian Light Responses under a Wide Range of Conditions.” Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 19 Apr. 2020, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jpi.12655.

88. He. “Effect of Restricting Bedtime Mobile Phone Use on Sleep, Arousal, Mood, and Working Memory: A Randomized Pilot Trial.” PloS One, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32040492/.

89. Chang, Anne-Marie, et al. “Evening Use of Light-Emitting EReaders Negatively Affects Sleep, Circadian Timing, and next-Morning Alertness.” PNAS, National Academy of Sciences, 27 Jan. 2015, www.pnas.org/content/112/4/1232.

90. MS;, Figueiro. “The Impact of Light from Computer Monitors on Melatonin Levels in College Students.” Neuro Endocrinology Letters, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21552190/.

91. M;, Sasseville. “Blue Blocker Glasses Impede the Capacity of Bright Light to Suppress Melatonin Production.” Journal of Pineal Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16842544/.

92. Clark, Ian, and Hans Peter Landolt. “Coffee, Caffeine, and Sleep: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Studies and Randomized Controlled Trials.” Sleep Medicine Reviews, W.B. Saunders, 30 Jan. 2016, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1087079216000150.

93. Alsene, Karen, et al. “Association Between A 2a Receptor Gene Polymorphisms and Caffeine-Induced Anxiety.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 14 May 2003, www.nature.com/articles/1300232.

94. Mora-Rodríguez, Ricardo, et al. “Caffeine Ingestion Reverses the Circadian Rhythm Effects on Neuromuscular Performance in Highly Resistance-Trained Men.” PLOS ONE, Public Library of Science, journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0033807.

95. Brzezinski, Amnon, et al. “Effects of Exogenous Melatonin on Sleep: a Meta-Analysis.” Sleep Medicine Reviews, W.B. Saunders, 11 Nov. 2004, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1087079204000607.

96. Braam . “Loss of Response to Melatonin Treatment Is Associated with Slow Melatonin Metabolism.” Journal of Intellectual Disability Research : JIDR, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20576063/.

97. Auger . “Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Intrinsic Circadian Rhythm Sleep-Wake Disorders: Advanced Sleep-Wake Phase Disorder (ASWPD), Delayed Sleep-Wake Phase Disorder (DSWPD), Non-24-Hour Sleep-Wake Rhythm Disorder (N24SWD), and Irregular Sleep-Wake Rhythm Disorder (ISWRD). An Update for 2015: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline.” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine : JCSM : Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26414986/.

98. Sletten, Tracey L, et al. “Efficacy of Melatonin with Behavioural Sleep-Wake Scheduling for Delayed Sleep-Wake Phase Disorder: A Double-Blind, Randomised Clinical Trial.” PLoS Medicine, Public Library of Science, 18 June 2018, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6005466/.

99. AP;, Facer-Childs. “Resetting the Late Timing of ‘Night Owls’ Has a Positive Impact on Mental Health and Performance.” Sleep Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31202686/.

100. Sander, Birgit, et al. “Can Sleep Quality and Wellbeing Be Improved by Changing the Indoor Lighting in the Homes of Healthy, Elderly Citizens?” Chronobiology International, Informa Healthcare, 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4673571/.

101. L;, Kirschen. “The Impact of Sleep Duration on Performance Among Competitive Athletes: A Systematic Literature Review.” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine : Official Journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29944513/.

102. TD. Bancroft, WE. Hockley, et al. “Overwriting and Intrusion in Short-Term Memory.” Memory & Cognition, Springer US, 1 Jan. 1970, link.springer.com/article/10.3758/s13421-015-0570-y.

103. Lin, Pi-Chu, et al. “Effects of Aromatherapy on Sleep Quality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Complementary Therapies in Medicine, Churchill Livingstone, 15 June 2019, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0965229919303735.

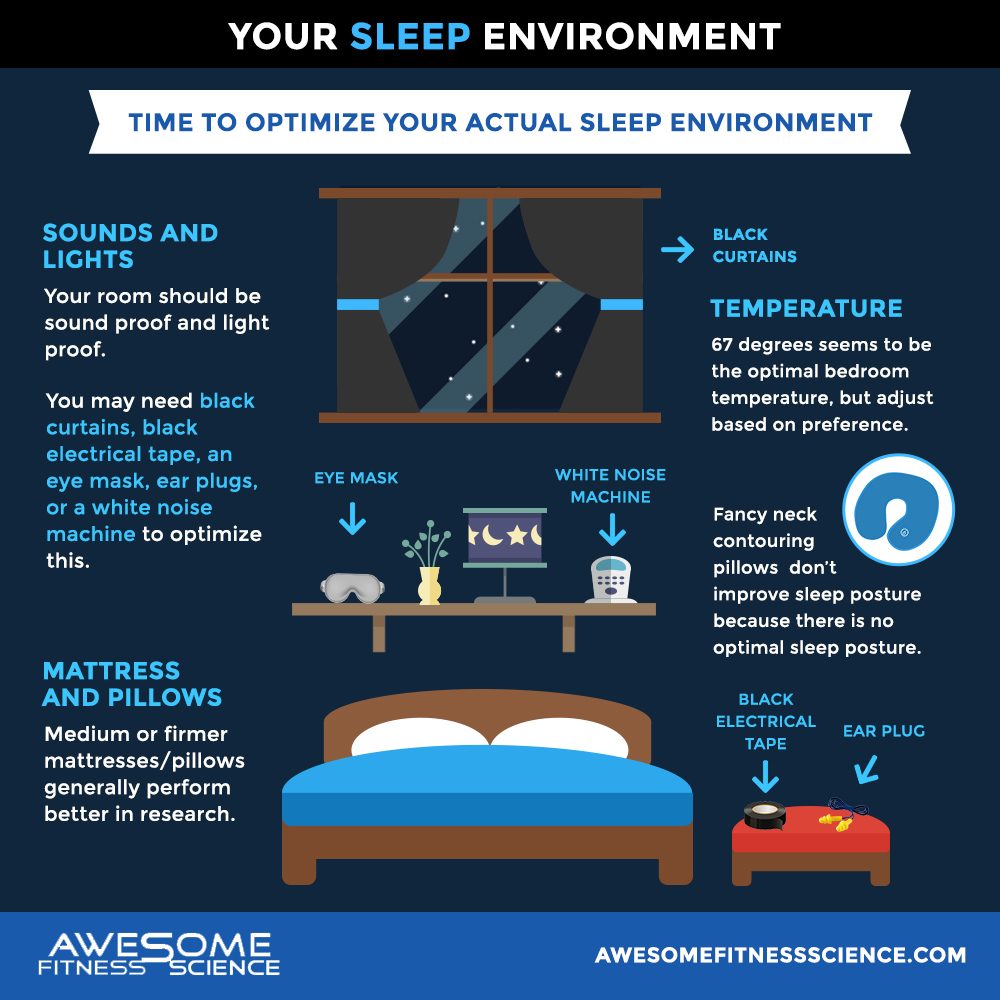

104. Jennum, P. “Sleep and Nocturia.” BJU International, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 11 Dec. 2002, bjui-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1046/j.1464-410X.90.s3.6.x.

105. Gilbert, Saul S, et al. “Thermoregulation as a Sleep Signalling System.” Sleep Medicine Reviews, W.B. Saunders, 2 Mar. 2004, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1087079203000236.

106. Raymann, Roy J. E. M., et al. “Skin Deep: Enhanced Sleep Depth by Cutaneous Temperature Manipulation.” OUP Academic, Oxford University Press, 11 Jan. 2008, academic.oup.com/brain/article/131/2/500/407617.

107. J. Waterhouse, Y. Fukuda, et al. “Effects of Feet Warming Using Bed Socks on Sleep Quality and Thermoregulatory Responses in a Cool Environment.” Journal of Physiological Anthropology, BioMed Central, 1 Jan. 1970, jphysiolanthropol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40101-018-0172-z.

108. Chepesiuk, Ron. “Missing the Dark: Health Effects of Light Pollution.” Environmental Health Perspectives, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Jan. 2009, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2627884/.

109. D;, Halperin. “Environmental Noise and Sleep Disturbances: A Threat to Health?” Sleep Science (Sao Paulo, Brazil), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26483931/.

110. Waye . “Effects of Nighttime Low Frequency Noise on the Cortisol Response to Awakening and Subjective Sleep Quality.” Life Sciences, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12493567/.

111. M;, Bodin. “Annoyance, Sleep and Concentration Problems Due to Combined Traffic Noise and the Benefit of Quiet Side.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25642690/.

112. Perron . “Sleep Disturbance from Road Traffic, Railways, Airplanes and from Total Environmental Noise Levels in Montreal.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27529260/.

113. U.. Beck, H.. Reinhardt, et al. “Ambient Temperature and Human Sleep.” Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, Birkhäuser-Verlag, 1 Jan. 1976, link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF01952376?LI=true.

114. PB;, Ebrahim. “Alcohol and Sleep I: Effects on Normal Sleep.” Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23347102/.

115. Lee, Hyunja, and Sejin Park. “Quantitative Effects of Mattress Types (Comfortable vs. Uncomfortable) on Sleep Quality through Polysomnography and Skin Temperature.” International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, Elsevier, 6 Sept. 2006, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0169814106001508.

116. “Neck Pain and Pillows – A Blinded Study of the Effect of Pillows on Non-Specific Neck Pain, Headache and Sleep.” Taylor & Francis, www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14038190600780239.

117. H;, Jacobson. “Subjective Rating of Perceived Back Pain, Stiffness and Sleep Quality Following Introduction of Medium-Firm Bedding Systems.” Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19674684/.

118. Physiotherapy Canada, www.utpjournals.press/doi/abs/10.3138/ptc.2010-13.

119. Gordon, Susan J., et al. “Pillow Use: The Behaviour of Cervical Pain, Sleep Quality and Pillow Comfort in Side Sleepers.” Manual Therapy, Churchill Livingstone, 7 May 2009, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1356689X09000459.

120. Gordon, Susan J, et al. “Pillow Use: the Behavior of Cervical Stiffness, Headache and Scapular/Arm Pain.” Journal of Pain Research, Dove Medical Press, 11 Aug. 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3004642/.

121. PMC, Europe. Europe PMC, europepmc.org/article/med/9608378.

122. Koul . “The Foam Mattress-Back Syndrome.” The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11198791/.

123. Gordon, Susan J, et al. “A Randomized, Comparative Trial: Does Pillow Type Alter Cervico-Thoracic Spinal Posture When Side Lying?” Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, Dove Medical Press, 2011, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3180478/.

124. Shields, N. “Are Cervical Pillows Effective in Reducing Neck Pain?” Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE): Quality-Assessed Reviews [Internet]., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 Jan. 1970, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK73379/.

125. Skarpsno, Eivind Schjelderup, et al. “Sleep Positions and Nocturnal Body Movements Based on Free-Living Accelerometer Recordings: Association with Demographics, Lifestyle, and Insomnia Symptoms.” Nature and Science of Sleep, Dove Medical Press, 1 Nov. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5677378/.

126. Tetley, Michael. “Instinctive Sleeping and Resting Postures: an Anthropological and Zoological Approach to Treatment of Low Back and Joint Pain.” BMJ : British Medical Journal, U.S. National Library of Medicine, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1119282/.

127. JA;, Pankhurst. “The Influence of Bed Partners on Movement during Sleep.” Sleep, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7973313/.

128. Blumen. “Effect of Sleeping Alone on Sleep Quality in Female Bed Partners of Snorers.” The European Respiratory Journal, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19574335/.

129. Richter, Kneginja, et al. “Two in a Bed: The Influence of Couple Sleeping and Chronotypes on Relationship and Sleep. An Overview.” Chronobiology International, Taylor & Francis, 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5152533/.

130. Troxel, Wendy M. “It’s More than Sex: Exploring the Dyadic Nature of Sleep and Implications for Health.” Psychosomatic Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, July 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2903649/.

131. Wilson . “Shortened Sleep Fuels Inflammatory Responses to Marital Conflict: Emotion Regulation Matters.” Psychoneuroendocrinology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28262602/.

132. Drews, Henning Johannes, et al. “Bed-Sharing in Couples Is Associated With Increased and Stabilized REM Sleep and Sleep-Stage Synchronization.” Frontiers, Frontiers, 5 June 2020, www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00583/full.

133. Mantua, Janna, et al. “Reliability of Sleep Measures from Four Personal Health Monitoring Devices Compared to Research-Based Actigraphy and Polysomnography.” MDPI, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 5 May 2016, www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/16/5/646/htm.

134. Peake, Jonathan M., et al. “A Critical Review of Consumer Wearables, Mobile Applications, and Equipment for Providing Biofeedback, Monitoring Stress, and Sleep in Physically Active Populations.” Frontiers, Frontiers, 28 May 2018, www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2018.00743/full.

135. Baron, Kelly Glazer, et al. “Feeling Validated Yet? A Scoping Review of the Use of Consumer-Targeted Wearable and Mobile Technology to Measure and Improve Sleep.” Sleep Medicine Reviews, W.B. Saunders, 20 Dec. 2017, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1087079216301496.

136. EJ. Lyons, ZH. Lewis, et al. “Systematic Review of the Validity and Reliability of Consumer-Wearable Activity Trackers.” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, BioMed Central, 1 Jan. 1970, ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-015-0314-1.

137. Kölling . “Comparing Subjective With Objective Sleep Parameters Via Multisensory Actigraphy in German Physical Education Students.” Behavioral Sleep Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26372692/.

138. K;, Draganich. “Placebo Sleep Affects Cognitive Functioning.” Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24417326/.

139. [email protected], Jean-Philippe Chaput, et al. “Sleep Duration and Health in Adults: an Overview of Systematic Reviews.” Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 15 Oct. 2020, cdnsciencepub.com/doi/10.1139/apnm-2020-0034.

140. Romdhani M;Hammouda O;Smari K;Chaabouni Y;Mahdouani K;Driss T;Souissi N; “Total Sleep Deprivation and Recovery Sleep Affect the Diurnal Variation of Agility Performance: The Gender Differences.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29864109/.

141. Rasch, Björn, and Jan Born. “About Sleep’s Role in Memory.” Physiological Reviews, American Physiological Society, Apr. 2013, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3768102/.

142. Xie, Lulu, et al. “Sleep Drives Metabolite Clearance from the Adult Brain.” Science (New York, N.Y.), U.S. National Library of Medicine, 18 Oct. 2013, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3880190/.

143. Mendelsohn. “Sleep Facilitates Clearance of Metabolites from the Brain: Glymphatic Function in Aging and Neurodegenerative Diseases.” Rejuvenation Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24199995/.

144. Cheng . “The Efficacy of Combined Bright Light and Melatonin Therapies on Sleep and Circadian Outcomes: A Systematic Review.” Sleep Medicine Reviews, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33962317/.

145. Soltanieh. “Effect of Sleep Duration on Dietary Intake, Desire to Eat, Measures of Food Intake and Metabolic Hormones: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials.” Clinical Nutrition ESPEN, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34620371/.